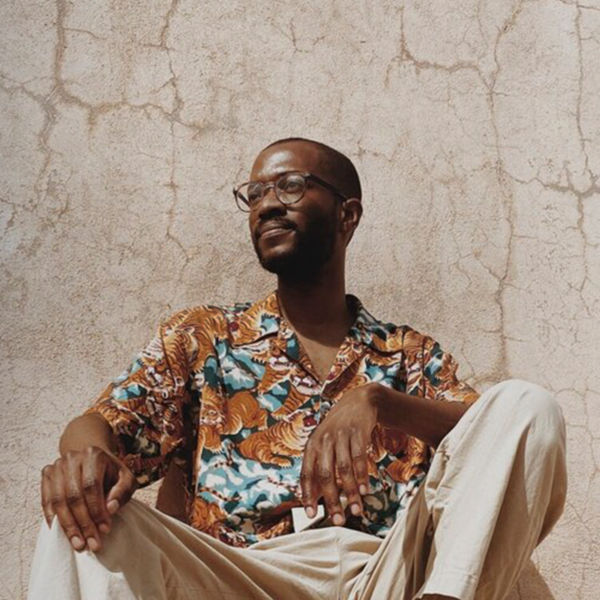

One look at the thumbprint of Hickory Edwards and you’ll know he’s found his calling: It has the shape of a paddle right in the middle. Edwards, 41, is a member of the Onondaga Nation (south of Syracuse, N.Y.), who uses paddling as a way to educate others about his Indigenous ancestors and their relationship with local waters.

That history of waterways as avenues of connection and shared knowledge, however, wasn’t always clear. Edwards only discovered their potential on a total whim. He wanted to know what lay beyond his own nation’s borders. So, he took to his hometown Onondaga creek and started paddling. The 2008 journey simply led him 12 miles to Onondaga Lake (often called America’s most polluted lake due to city sewage and industrial dumping). But the trip inspired him to create the Onondaga Canoe and Kayak Club, a nonprofit designed to “relearn the ancient water trails that were once common knowledge to our native grandfathers.”

The club’s first crusade: organizing a group in 2013 to paddle from the Onondaga Nation down the Hudson River to New York City to celebrate the 400th anniversary of the Two Row Wampum, a landmark treaty between the Haudenosaunee and the Dutch. A year later, he rallied a group to paddle from Tully, N.Y., to Washington, D.C., along the Tioughnioga, Chenango and Susquehanna rivers into Chesapeake Bay, and then walk two days across Maryland to attend the opening of a National Museum of the American Indian exhibit. He also led a trip on the Northern Forest Canoe Trail. In May 2022, he came back to the Susquehanna, bringing a mix of Onondaga and other Native Americans on a 100-mile paddle to its near confluence with the Chenango River.

Fifteen years on, the Club has only amassed more canoes and kayaks, ever dedicated to retracing the traditional network of waterways connecting the original Five Nations of the Haudenosaunee Confederacy, while exposing new people to the waters he loves (including his 10-year-old daughter, ElliRose).

Public Lands recently caught up with Edwards between the handful of trips he leads each year, noting his ideas for future expeditions designed to get people outside, educate them on the region’s Native American history, and get them to care about the environment they’re traversing in the process.