Learning how to build equalized gear anchors is one of the first and most important steps for a budding trad climber. Basically, a gear anchor is a handful of pieces of protection placed in the rock and strung together with webbing or cord. When an anchor is “equalized,” that means the weight of a hanging climber will be evenly distributed between each piece.

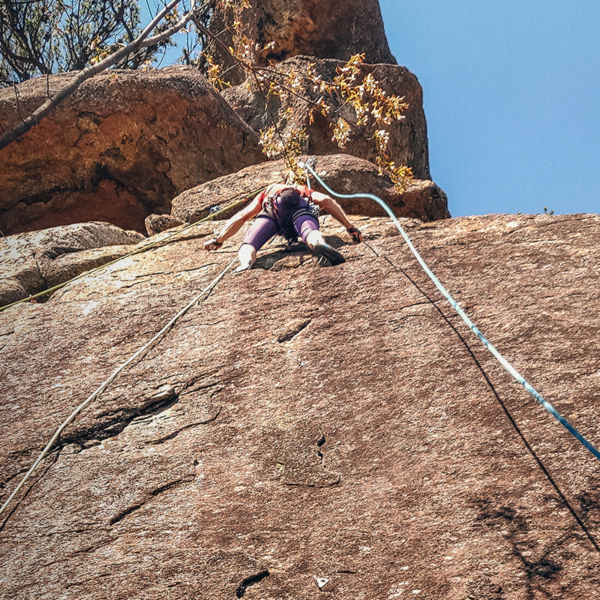

Gear anchors are handy for setting up topropes in terrain where bolted anchors aren’t available and also for building ground anchors to protect lightweight climbers from getting launched upward if their heavier partner falls. But they’re most commonly used for belaying on multipitch trad routes. Most multipitch climbs have recommended anchor-building spots where a ledge provides a comfortable stance. However, the beauty of gear anchors is that you can build them anywhere you can find good cracks and solid gear placements, letting you split up the pitches however you please.

Anchor building is as much an art as it is a science, and you can spend a lifetime nerding out about the detailed physics, material advantages, and clever variations that go into it. (Some climbers go so far as to save photos of anchors they’re particularly proud of.) But you don’t have to get that deep to build safe, solid anchors that will work in a variety of scenarios.

In this guide, we’ll cover one of the most common and versatile styles of gear anchor: The equalized cordelette anchor. We’ll also refresh your memory on some anchor basics.

Contents

- Anatomy of an anchor

- Qualities of a good anchor

- How to build an equalized cordelette anchor

Anatomy of an Anchor

Anchor Points

The actual protection connecting your anchor to the rock—in this case, pieces of trad gear.

Leg

A length of soft material, often cordelette, connecting each anchor point to the masterpoint.

Masterpoint

The loop at the center of the anchor that the climber clips into and belays off of. Tugging on this loop puts equal force on all the anchor points in the system. In a cordelette anchor, the loop is usually created by an overhand knot on a bight.

Qualities of a Good Anchor

You’ll hear climbers describe good gear anchors as “SERENE,” though the real acronym that guides and instructors like to use is “SERENA” or “SERENE-A.” It can be handy to run through each letter after you build an anchor to check your work.

- The anchor should be strong enough to hold a fall from a heavy climber.

- It should ensure the load is equalized, or evenly distributed between all the anchor points in the system. In other words, when the anchor is loaded, all legs should come taut at once.

- It should have redundant elements in case one piece of gear or leg fails.

- It should be simple, efficient to set up, and easy to double-check.

- There should be no extension or sudden shock-loading if one element fails.

- The anchor’s legs should form angles that are less than 60 degrees to one another, which minimizes dangerous loading on your anchor points.