Trixie Bennett is president of the Ketchikan Indian Community (KIC), a federally recognized tribe of more than 6,000 people in southeast Alaska. Though now based in the tribe’s headquarters of Ketchikan, Bennet grew in Wrangell at the mouth of the Stikine, a regional river that’s been her people’s ancestral homelands for thousands of years. It’s part of what the Alaskans who live here call the Salmon Coast: three enormous river systems in the Tongass National Forest that make up one of the last intact ecosystems of this scale on the planet.

These rivers host some of the few remaining wild salmon runs, and scientists have called the old-growth forests shading them the “lungs of the country,” as America’s carbon-sink version of the Amazon. The region hosts the largest known concentration of bald eagles; is a stronghold for brown bears, which have dwindled in the lower 48; and anchors Alaska’s biggest tourism economy, from wildlife-watching, hunting, fishing and sightseeing, to cultural experiences offered by the Indigenous tribes.

Beyond the health of Tongass (the largest national forest in the U.S.), across the border, Canadian mining companies refer to the region as the Golden Triangle, where a series of open-pit gold and copper mines mark the rugged landscape with colossal, notoriously leaky toxic-waste storage facilities. Canada is currently poised to develop nearly 6,000 more square miles of claims, including at the headwaters of the Stikine. Mineral extraction there would be the river’s death knell as arsenic, sulfuric acid, and other toxins leach into the water, slowly wiping out the fish, plants, animals that depend on them—and way of life for an entire people.

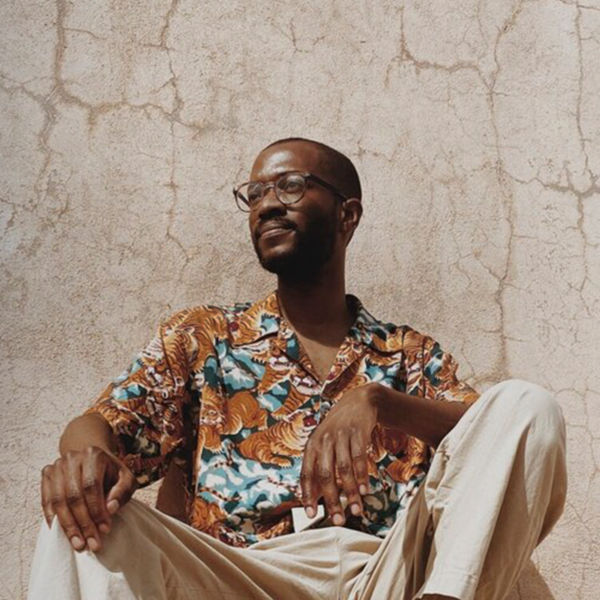

Bennett, who’s also a traditional healer and owns the medicine shop Tongass Tonics, is leading the Ketchikan Indian Community’s fight to save the Stikine, Unuk, and Taku rivers. KIC and other tribes, municipalities, organizations, and individuals are bringing resolutions to President Joe Biden and Prime Minister Justin Trudeau later this fall to demand Canada agree to pause its rush to develop mining on immense portions of shared salmon river systems, and to ban dams used for problematic mine tailings.